During morning Superbike practice, while approaching turn one at New Hampshire International Speedway, Tom Kipp pulled in the clutch lever on his Yamaha YZF750R with his left hand, tapped the gearshift lever in staccato rhythm with his left foot to backshift four gears, and released the clutch lever while also squeezing the front brake with his right hand and feathering in a little bit of rear brake with his right foot. The bike’s five-valve, four-cylinder engine shrieked in high-pitched protest as the back end of the motorcycle slid sideways and Kipp leaned to the left to set up for the entrance to the turn. The Ohio rider repeated the same maneuver virtually every time he came screaming into that turn.

It was one of the most breathtakingly cool things I ever saw someone perform on a motorcycle, and my amazement was shared by everyone else sitting in the grandstand outside NHIS’s turn one. Some stood and pointed, some oohed and aahed, and some just sat in stunned silence with their jaws agape.

I remember going down in the paddock after the session and expressing my extreme pleasure to Yamaha’s Tom Halverson in witnessing what Kipp repeatedly did for lap after lap while going into turn one. Halverson politely smiled and said, “Yeah, we’re trying to get him to stop doing that.” The statement initially caught me by surprise, and then continued to resonate in my ears as I watched Kipp earn the pole with a fastest lap of 1:13.743, and then notch a third-place finish behind Miguel Duhamel in second and Doug Chandler who won. That was on June 16, 1996, and it wasn’t until years later when I followed up with Halverson and asked him why he and his Vance & Hines Yamaha team wanted to get Kipp to “stop doing that.” The stress and strain on the engine and transmission of Kipp’s Superbike, increased clutch wear, and increased wear to the rear Dunlop tire on his bike were, to me, obfuscated by my absolute delight in seeing Kipp “backing it in” for lap after lap.

This was long before the practical usage of back-torque-limiting or so-called “slipper” clutches on motorcycles. Today, the technology is ubiquitous in the MotoAmerica paddock, and even most of today’s street-going sportbikes are equipped with slipper clutches.

Engine braking is a characteristic on virtually every four-stroke motorcycle, and it is most noticeable whenever you roll-off the throttle. Even before you apply the brakes, a motorcycle will decelerate due to engine braking, which is multiplied even more by the negative engine torque created when you downshift or “backshift” the transmission. In other words, when let off the gas and shift to a lower gear, the bike feels like it’s being held back even before you touch the brakes.

Using a motorcycle’s engine braking to slow a bike down does reduce brake usage and enable the brake pads to last a little longer. However, as Tom Halverson alluded to so many years ago, it puts a huge strain on the bike’s clutch plates and transmission, as well as on the engine itself as the crankshaft, pistons, valvetrain, and other rotating engine parts suddenly and violently reach stratospheric revolutions. Oh, and while that big skidmark that the rear tire leaves on the asphalt as the rear wheel locks up and the back end of the bike “steps out” is a sight to see, it’s unnecessary tire wear, not to mention an unnecessary risk of crashing.

The main purpose of a slipper clutch is to reduce the effect of engine braking when the rider decelerates. As the braking force transmitted from the engine through the chain drive and to the rear wheel causes the rear tire to lose traction, the slipper clutch is designed to partially disengage or “slip” when the rear wheel tries to drive the engine faster than it would under deceleration. And then, when the engine speed and rear-wheel speed become compatible, the slipper clutch re-engages.

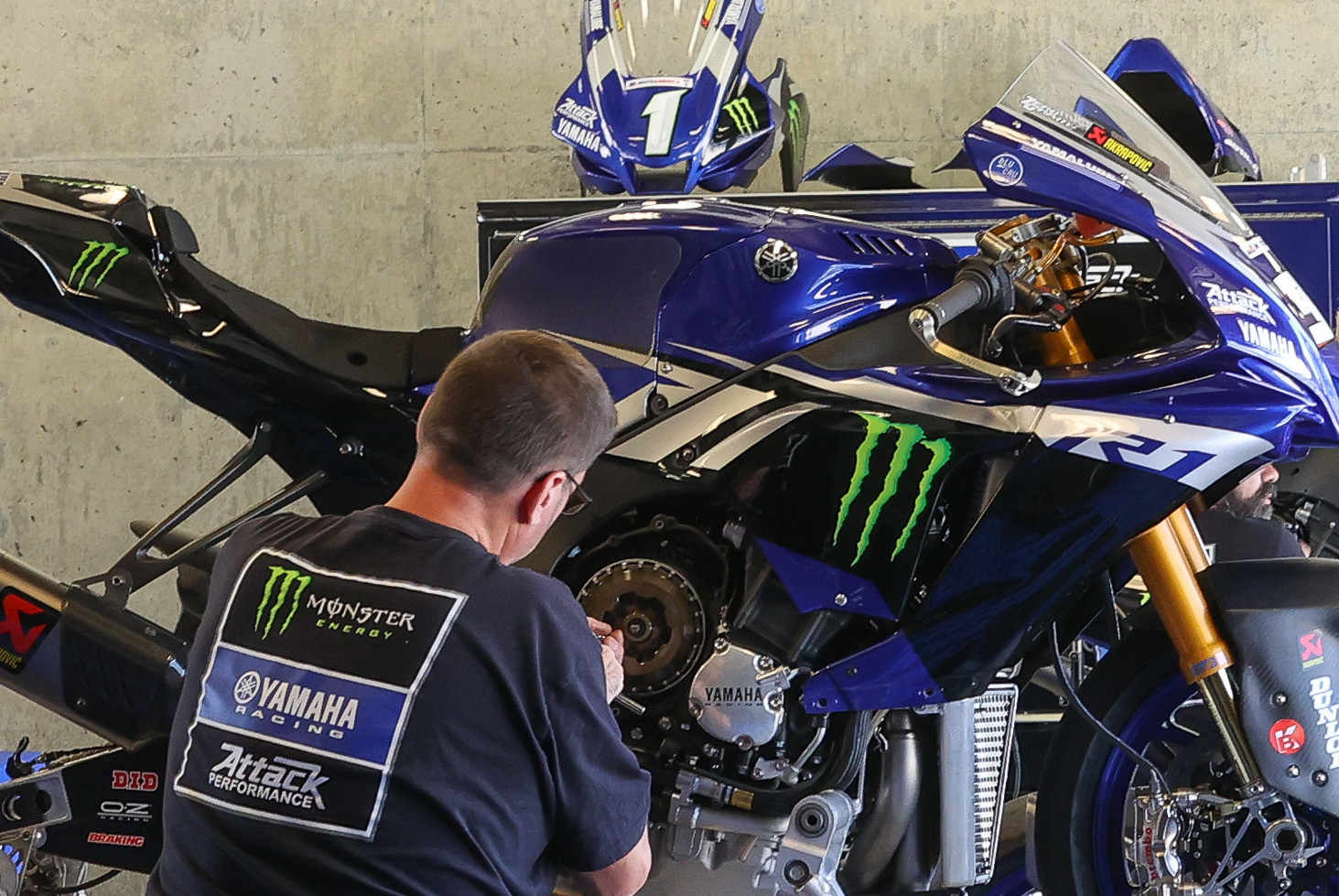

In motorcycle road racing, aftermarket slipper clutches like those made by companies like Suter Racing Products reduce the strain on the gearbox, prevent over-revving of the engine, and even help maximize suspension performance. The result is more stable braking, more precise corner entry, optimal corner exit speed, and most importantly, faster lap times. Plus, they can be simply and easily adjusted to different conditions and rider styles.

Along with slipper clutches, the motorcycles that compete in the HONOS Superbike class also have Electronic Control Units (ECUs) that feature adjustable engine-braking capabilities. Manipulation of the ECU as well as the slipper clutch are all part of tuning a modern Superbike.

To purchase tickets for all MotoAmerica events, click HERE

For information on how to watch the MotoAmerica Series, click HERE

For the full 2021 MotoAmerica Series schedule, click HERE